Project Showcase: Working Safely with Sharps

In this project showcase (a new series on the ETO blog), we’re highlighting the Working Safely with Sharps scenario-based training module. Completed in February 2024, this project was a collaboration between Environment Health and Safety (EHS), FASE Health and Safety, and the Education Technology Office (ETO). Our goal was to transform an existing one-hour training presentation into an interactive digital learning experience.

This project's unique blend of storytelling, instructional design, and multimedia production sets it apart from some of the other types of projects the ETO has worked on in the past. We're hoping that the collaborative approach generates an impactful learning experience that will resonate with learners while promoting safe practices. The final module is a self-directed learning experience that can be shared flexibly, allowing for learners to reference the module as assigned, as needed, or “just-in-time” for their lab work.

Want to explore the module? Try out the Working Safely with Sharps Module or Access the media assets in this module directly.

Who worked on this project?

ETO Staff

Subject Matter Experts (SMEs)

Stephanie Tanninen-Bakir (Research Oversight & Compliance Office)

![]() What is the difference between learning and training? Most of the ETO’s projects are focused on learning; we build digital learning experiences that promote the absorption of knowledge, increasing learner abilities and enabling transfer to other applications and contexts. Training, in contrast, is more prescriptive and often includes a demonstration of a procedure that instructs the learner. In a training module, you’ll notice more of a focus on observable and measurable behaviours and outcomes, especially in job-related skills. To contextualize this practice within the Working Safely with Sharps project, the measurable outcomes would be a decrease in incidents with sharps (specifically the types covered in the module) and an increase in reporting of incidents such as near-misses (which may have tended to be under reported). Both training and learning are essential aspects of the education process, but we design the experience differently depending on the specific goals of the project.

What is the difference between learning and training? Most of the ETO’s projects are focused on learning; we build digital learning experiences that promote the absorption of knowledge, increasing learner abilities and enabling transfer to other applications and contexts. Training, in contrast, is more prescriptive and often includes a demonstration of a procedure that instructs the learner. In a training module, you’ll notice more of a focus on observable and measurable behaviours and outcomes, especially in job-related skills. To contextualize this practice within the Working Safely with Sharps project, the measurable outcomes would be a decrease in incidents with sharps (specifically the types covered in the module) and an increase in reporting of incidents such as near-misses (which may have tended to be under reported). Both training and learning are essential aspects of the education process, but we design the experience differently depending on the specific goals of the project.

What was different about this project?

In each showcase, we’ll highlight what made the project unique. In this project, the ETO introduced:

1. Use of scenario-based learning to show instead of tell

This project differs from other projects Anna previously worked on at the ETO because it incorporated scenario-based learning to “show” learners instead of “tell” them about Sharps Safety. Scenario-based learning incorporates storytelling, making content more engaging and impactful for learners. In the context of Sharps Safety, the scenarios allowed learners to experience the consequences of their decisions in a risk-free environment. In addition, the scenarios were strategically sequenced within the modules to allow learners to assess and reflect on their own prior knowledge about Sharps Safety, before moving on to the content presentation (which included videos with step-by-step instructions for handling sharps in situations that reflected the situations presented in the scenarios). An additional component is downloadable Quick Reference Guides (note: access requires authentication with U of T's O365 account), designed to be used for performance support outside of the module.

Beyond the module. After completing at least one of the scenarios, Anna encourages learners to decide for themselves how well the scenario reflects real-life situations and whether they feel that this would be a memorable way to learn about Sharps Safety. This activity could be completed with learners either synchronously in person, online, or asynchronously (e.g., through a discussion board).

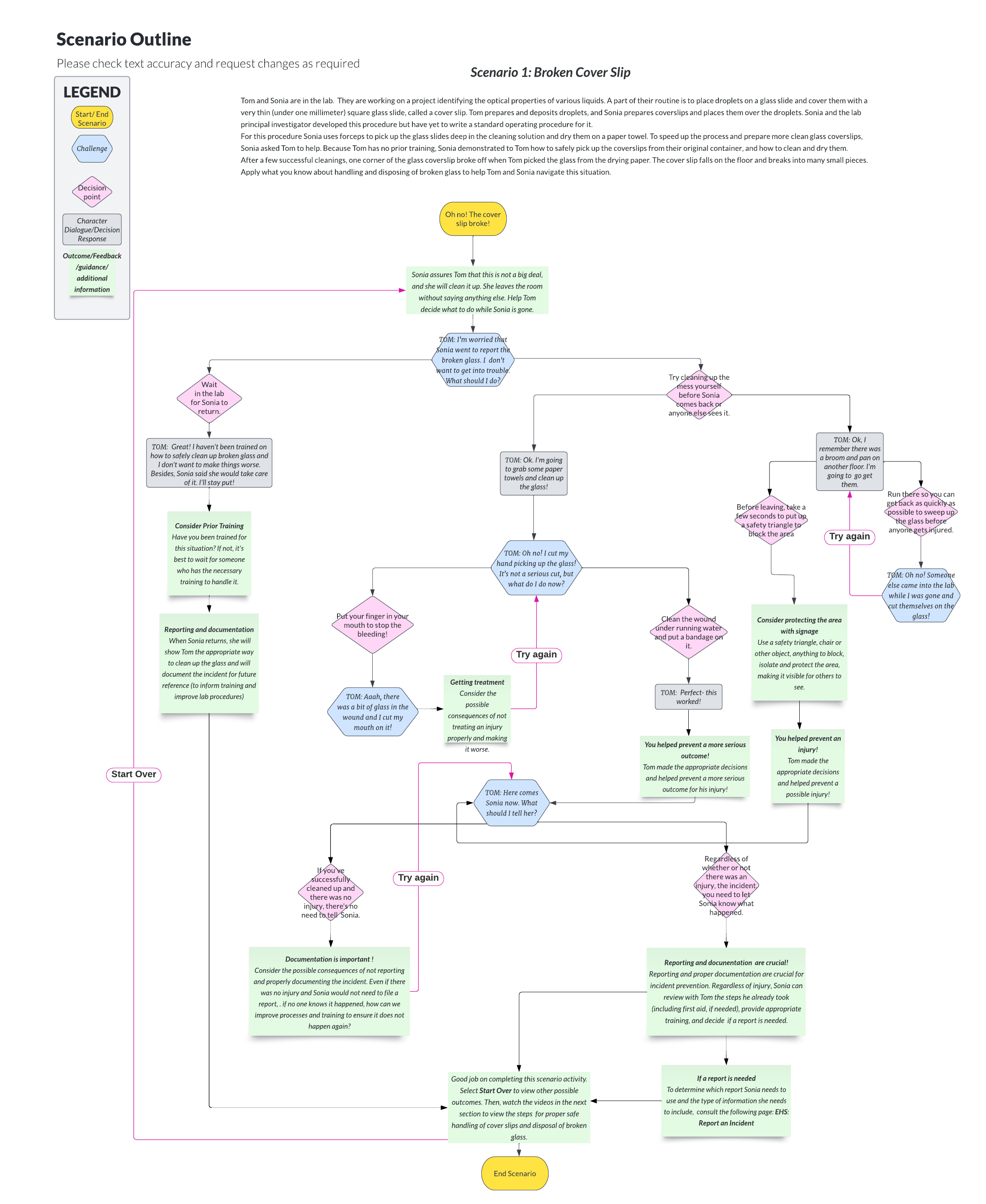

What we learned. In developing a scenario outline to share with the SMEs for collecting feedback, Anna initially used LucidChart to show all the potential paths . In retrospect, a simpler tool would have been better. She has since experimented with Twine and is currently looking into even simpler options.

Example Scenario Outline (using LucidChart): Sharps Scenario 1: Broken Cover Slip.

Caption: The example above illustrates the complexity of even a simple branching scenario. Select on the image to zoom in (functionality may be limited on some devices).

2. Use of comics to immerse learners in the experience

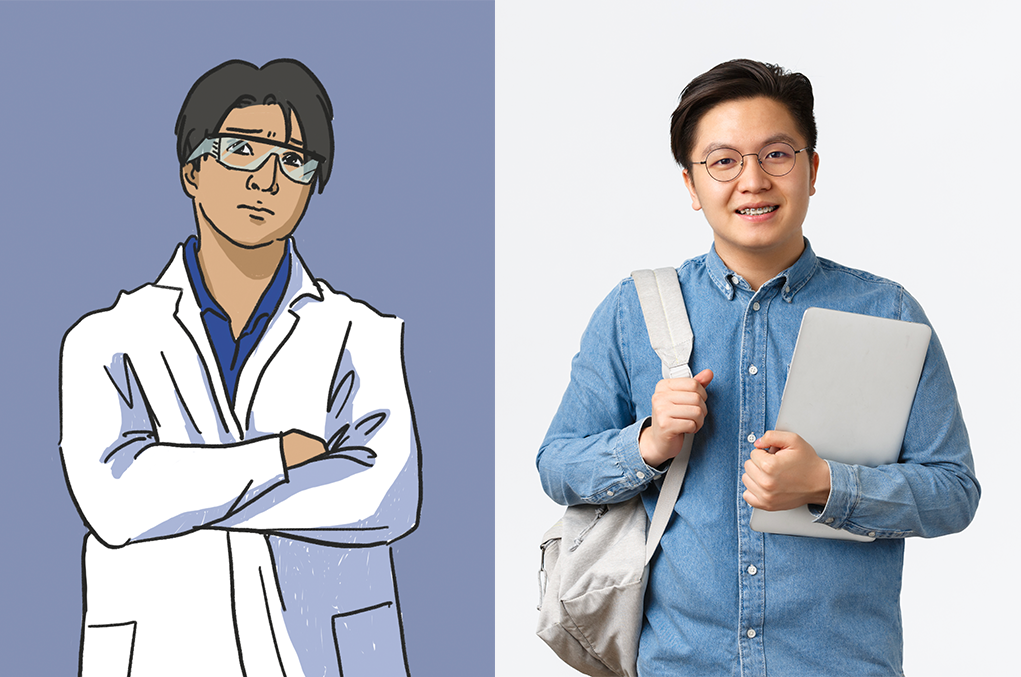

The scenarios included in the module were selected for training purposes because they are based on injuries that commonly happen around labs. A priority for the project was to have learners see themselves in the situations. This was a perfect opportunity to use comics as a medium for learning. When reading comics, the reader immerses themselves right into the situation. This is a different experience than watching a movie (video is also used in this project, but sparingly), where you may relate to the story, but you still perceive it as someone else’s experience instead of your own. Scott McCloud describes this immersion in his book, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, as the masking effect; where characters with simple but recognizable designs (the author calls these iconic characters) allows the reader to project themselves into the story by using characters as a mask. To maximize the chances that learners will embed themselves in the scenarios, we opted for creating cartoons of the students in different situations rather than using photos or videos. In the side-by-side image below, you’ll see Cheryl’s work in Wei’s transformation from stock student image to comic character.

Example 01: Developing a learner comic (Wei)

Caption: LEFT: First draft sketch of Wei (later refined to reflect correct lab-attire) RIGHT: Inspiration stock photo of an Asian student

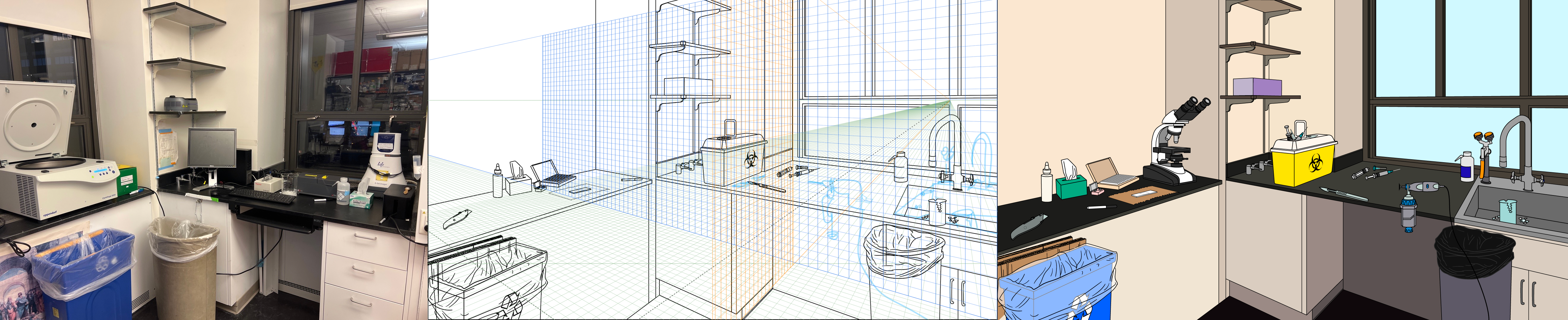

Once Cheryl had designed the people, she turned to the space in which the students were acting. For full effectiveness, the masking effect requires the characters to be placed in realistically detailed backgrounds. This amplifies the reader-character connection, as the contrast emphasizes the otherness of the setting and the status of the character as an empty canvas. Our backgrounds needed enough details to be recognized as a familiar setting to our learners (so they could easily imagine themselves being in the exact situation of the scenarios) but generic enough that it would resonate across different learner groups over multiple terms. We took many reference photos of the labs around FASE and created background illustrations.

Example 02: Developing a lab background from lab photo to generalized illustration

Caption: LEFT: Reference Photo; existing lab space; MIDDLE: Sketch in progress, using 2-point perspective for the comic, RIGHT: Final art, space is generalized but includes common lab elements

Beyond the module. Before learners interact with the module (e.g., via Quercus), Cheryl encourages learners to create their own comics about the topic (or their feelings about the topic) as an icebreaker to raise learner engagement. This might also be a directed, interactive activity (individually or in a group) during an in-person session. This activity can be as complex or as simple as the artistic skills of the learners (e.g., something as short as a single panel with stick figures and some text bubbles. After the module, the learners can look back to these comics to help with their reflection.

3. Use of formal scripting to enhance collaboration with Subject Matter Experts (SMEs)

Caption: This video demonstrates how to dispose of blades. You can also review the complementary guide to disposing of blades.

Beyond the module. Digital pre-training complements in person, hands-on training. By assigning the module ahead of the experience, learners can use their time in a lab to practice what was demonstrated in the module. In their instructor roles, SMEs can focus on providing instruction and support to students in situ, reducing the time required to explain a procedure or process and maximizing the students’ hands-on experiences.

What we learned. While filming the videos for this project, Marisa learned firsthand about the importance of having storyboards and scripts completed and finalized ahead of filming. With scenario-based video content, the need for detailed planning became even more evident during filming and it was particularly crucial to convey the proper techniques and safety procedures related to sharps handling, since accuracy and clarity were critical.

![]() Why use scenario-based learning? Anna hopes that anyone viewing this project is inspired to try scenario-based learning (and not only for health and safety training or other high-risk task training). Scenarios can be used to develop complex decision-making skills in leadership training and professional skills training and are well-suited to situations where you want to provide practical ways for learners to apply theoretical knowledge in a real-world situation.

Why use scenario-based learning? Anna hopes that anyone viewing this project is inspired to try scenario-based learning (and not only for health and safety training or other high-risk task training). Scenarios can be used to develop complex decision-making skills in leadership training and professional skills training and are well-suited to situations where you want to provide practical ways for learners to apply theoretical knowledge in a real-world situation.